In the early 1960s, America was gradually sinking into the Vietnam conflict. Washington supported the government of South Vietnam, which was fighting against Communist forces in the North, sponsored by the Soviet Union. For most citizens, this seemed like a distant issue—an attempt to contain the spread of communism somewhere on the other side of the world. The world saw it as just another chess match in the Cold War. But with each passing year, U.S. involvement deepened, and the number of wounded and killed soldiers grew. It was then, amidst the ordinary quiet of American life, that the first voices of protest began to sound. Here is on new-york-yes.com the story of how those voices grew in New York and when they reached their maximum volume.

The Seeds of the Anti-War Movement in the U.S.

At first, the protests were isolated and barely noticeable—a few dozen students, teachers, and priests who questioned the wisdom of intervening in Vietnam’s internal affairs. But within a few years, those quiet doubts turned into a powerful wave of resistance that brought hundreds of thousands of people into the streets. In 1963, a shocking photograph circulated worldwide—a Buddhist monk engulfed in flames, sitting calmly in the middle of a street in Saigon. This act of self-immolation became a symbol of the despair and profound injustice reigning under the pro-American Premier Ngo Dinh Diem. It was then that America suddenly saw that in Vietnam, it was not just the fire of war that was burning, but the fire of human suffering.

Despite the growing concern, the Kennedy administration did not stop. The President continued to send advisors and equipment, trying to keep the situation under control. In one of his last interviews, given to journalist Walter Cronkite in September 1963, Kennedy spoke cautiously but frankly:

“In the final analysis, it is their war. They are the ones who have to win it or lose it. We can help them, we can give them equipment, we can send our men out there as advisers, but they have to win it, the people of Vietnam, against the Communists.”

However, aid increasingly resembled intervention. America was stepping further into the conflict. The anti-war movement was just beginning to ignite, but the fire that the Buddhist monk had lit in Saigon had already spread to the hearts of Americans.

Rising Tensions

After the death of John F. Kennedy, America sank deeper and deeper into the Vietnam mire. The new president, Lyndon Johnson, took a decisive step in March 1965—he sent the first contingent of combat troops to Vietnam. To most Americans, this still didn’t look like a disaster, but on college campuses, a different war was already boiling over—a war for conscience.

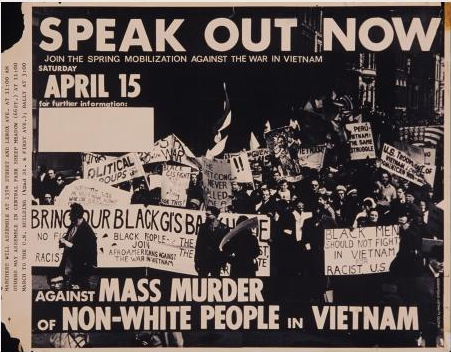

That same year, the first organized protests against the war began to appear in student circles. Young people, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, held teach-ins—discussions dissecting what was really happening in Vietnam. By the spring of 1965, people took to the streets. The leftist student organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) called for a large-scale march in Washington. On April 17, over 15,000 people marched onto the National Mall. But the protest was not limited to the capital. In June of the same year, 17,000 people filled Madison Square Garden in New York. Speakers included Senator Wayne Morse, who was unafraid to openly criticize the President, activist Bayard Rustin, and the famous pediatrician Benjamin Spock, whose popularity among American families made him a symbol of moral protest.

President Johnson tried to downplay the movement’s significance, assuring Congress that there was no serious division in the country. But on the very day he spoke those words, police arrested 350 demonstrators near the Capitol.

Yet the anti-war wave didn’t stop—it only grew. By late 1965, even high school students had joined the protest. In Des Moines, Iowa, 13-year-old Mary Beth Tinker, her brother John, and their friend decided to express their dissent by wearing black armbands of mourning to school. The administration ordered them to remove the armbands; the children refused and were suspended. This seemingly minor incident became a precedent. The Tinker family, supported by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), filed a lawsuit. The case, Tinker v. Des Moines, reached the Supreme Court in 1969. The Court made a landmark decision: students do not shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate.

Meanwhile, in 1966, the war raged on—and the resistance movement grew with it. By late March, protests swept across the entire country: New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Ann Arbor, and dozens of other cities. Thousands gathered in Central Park in New York—these were no longer just student revolts but a genuine popular movement against the war, becoming a symbol of a new, conscious America.

The Largest Protest in New York

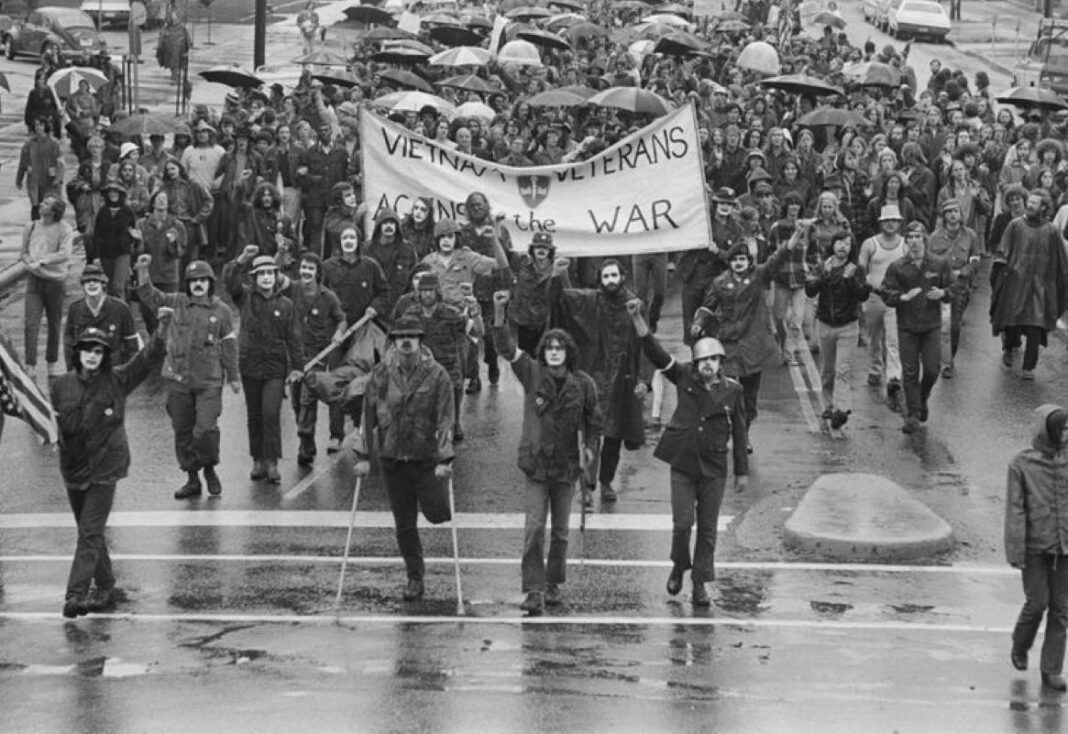

The spring of 1967 was the moment the anti-war movement in the U.S. reached its peak. On April 15, New York became the stage for a historic event—the largest protest against the Vietnam War, drawing between 300,000 and 400,000 people. It was the day when different generations and social strata merged into a single voice of protest—the voice of a nation that no longer wanted to stay silent.

Columns of demonstrators stretched across all of Manhattan, from Central Park to the UN headquarters. They marched past Times Square, carrying signs with slogans like “Bring the Troops Home,” “Stop the War in Vietnam,” and the iconic “Make Love, Not War.” The sounds of songs, drums, and chants rang out over the city—and at the center of this human sea marched Martin Luther King Jr., Harry Belafonte, Dr. Benjamin Spock, and other moral authorities of the time.

The movement was headed by 82-year-old New York activist A. J. Muste, a symbol of the old school of peacemakers who represented the link between generations—from pacifism veterans of the 1930s to students of the counterculture era.

The marchers walked for five hours in the rain but did not disperse. When King took the stage near the UN building, he spoke not in anger, but with deep pain and love:

“I speak against America not in anger, but with anxiety and sorrow in my heart, and above all with a passionate desire to see our beloved country be a moral example to the world.”

His words broke the silence between the civil rights and anti-war movements—they now became a united front. For many, it was a moment of awakening: the Vietnam War was not a question of politics, but a question of conscience.

But the establishment reacted differently. The very next day, Secretary of State Dean Rusk claimed the anti-war protests were being directed by Communists. The New York Times covered the event with the dismissive headline: “Many Draft Cards Burned—Eggs Thrown at Parade.” It seemed the government and the media were trying to minimize the significance of what had happened.

Nevertheless, history set the record straight. The war would drag on for eight more long years, claiming tens of thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese lives. But it was that April, in the New York rain, that America first massively said “no” to war. And that day forever remained a symbol of the nation’s moral awakening.

The Mixed Public Stance

Anti-war voices from prominent figures in politics, culture, and sports grew increasingly louder. Among them:

- Martin Luther King Jr.

He was one of the first national leaders to openly oppose the war. Starting in the summer of 1965, he condemned the fighting as morally indefensible and intrinsically linked to racial injustice in the U.S. King stressed that African-American youth were more likely than whites to be sent to the front lines and suffered greater casualties, while being denied equal rights and opportunities at home.

- Muhammad Ali.

The world heavyweight boxing champion took one of the boldest steps, publicly refusing military service on conscientious grounds. He was stripped of his championship title, and his legal battles lasted for years, but the Supreme Court ultimately acquitted Ali. His stance became a symbol of moral defiance and commitment to one’s principles.

- Jane Fonda.

The popular actress and daughter of the legendary Henry Fonda also joined the peace movement. Her trip to North Vietnam caused a huge controversy—some saw her courage, while others accused her of treason. Despite the controversy, Fonda remained an active opponent of the war, speaking at numerous rallies and gatherings.

- Joan Baez.

The famous folk singer used her stage as a platform for peace. She sang at protests, participated in civil campaigns, and later helped Vietnamese refugees, known as the “boat people.”

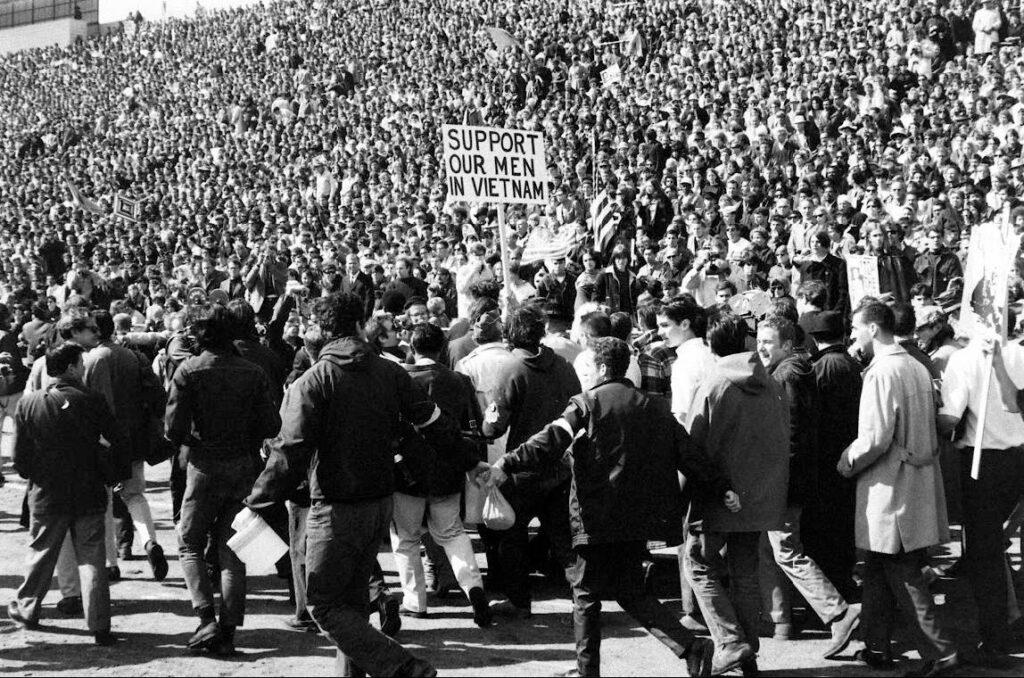

However, the peace movement did not have unanimous support. A segment of society, especially conservative groups, sharply condemned the protesters, labeling them “un-American.” Counter-demonstrations and, at times, violent clashes often took place in cities.

Nevertheless, the demonstrators’ actions significantly influenced the U.S. political discourse and increased pressure on the government to review its policy in Vietnam.